In the face of rising inflation, interest rates and the most recent tech layoffs, it can feel like another recession is just around the corner. But how true is this?

With all of the talk around the potential for a recession, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s 2008 all over again.

However, there have been a combination of factors that have come together at the same time to raise these concerns.

Coming out of the lockdown-influenced economic downturn after Covid, we have been hit with supply chain issues, while Brexit continues to play a role in economic uncertainty.

And Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has only truncated the matter, bringing a new level to the energy supply crisis that had emerged after Covid.

Elsewhere, recent layoffs in Twitter, Meta and Stripe have added extra anxiety that the tech industry, which is important not only in economic terms but in showcasing Ireland’s reputation as an IT hub, could be on the verge of a collapse.

But are we really on the verge of a recession? Or is it just a small wobble amidst our unsustainable levels of growth?

The importance of definitions

The first bone to pick in the discourse surrounding a recession is its actual definition.

If we were to go with its strictest definition, a technical recession would be two successive quarters of decline in a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). If we were to take this as the only barometer of a recession, then most of the world’s economy would have been in a recession during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But, as we saw, the economy quickly rebounded following the cessation of lockdown and the re-opening of the economy. While most of the world was technically in a recession, it didn’t necessarily feel as damaging, mostly due to extensive protections for those who lost their job and the temporary conditions surrounding the cause of the recession.

In comparison to other recessions, it wasn’t caused by banking malpractice or a massive reduction in the value of assets, but rather around the economy grinding to a halt and being unable to perform as it would normally have been able to.

The recession was also short lived - in the US, the National Bureau of Research concluded that the recession in the immediate wake of the pandemic lasted only two months, the shortest in history.

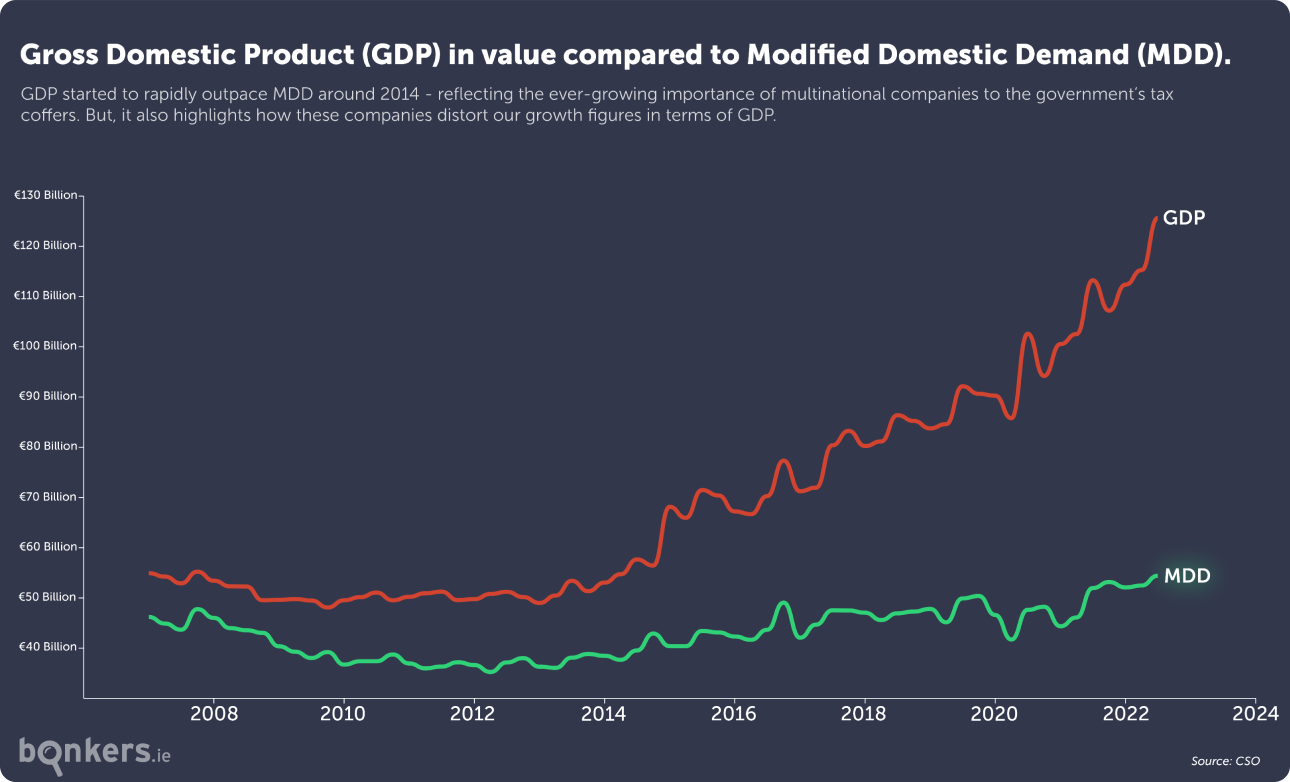

However, we all know the multiplying effect that GDP has on Ireland due to our special relationship with multinational companies and the repatriation of profits, perhaps best illustrated by our contentious 26.3% GDP increase in 2015.

As such, it’s important to have a more broad understanding of what constitutes a recession. This can be a contentious topic, as there are a multitude of factors that can categorise it – and different countries and entities define it differently.

The EU, for example, broadly follows the US-centric model, but due to its transnational nature, has to take more factors into account.

The Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), the EU’s main economic think tank, acknowledges that while two consecutive quarters of a fall in GDP does normally constitute a recession, it’s not a “fixed rule”.

Indeed the CEPR also takes into account:

- Quarterly employment

- Monthly industrial production

- Quarterly business investment and consumption

So, while two quarters of contraction is a strong sign of recession, it isn’t the be-all and end-all in terms of economic forecasts.

The factors contributing to uncertainty

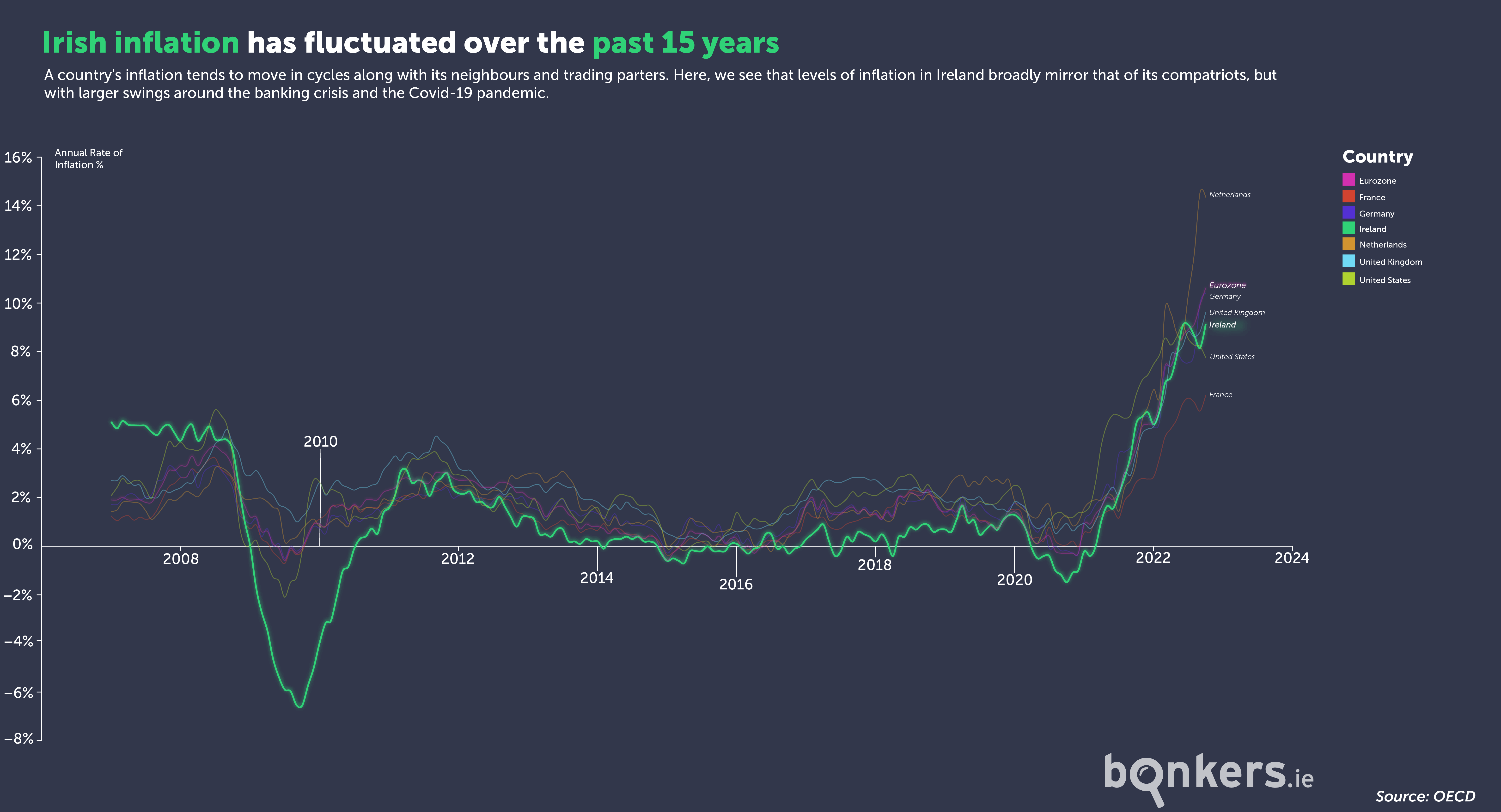

Across Europe, economies are bracing for the lasting effects that inflation is going to bring.

Bigger, more manufacturing-based economies such as Germany, France and the UK rely heavily on natural gas for their output, and thus are far more exposed to the effects of rampant energy inflation.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) predicts that major economies, such as Germany and the UK, will see their GDP drop to -0.30% and -0.40% respectively in 2023. Ireland’s prediction is rather rosier: 3.8% growth in 2023 and 3.2% in 2024.

Over the whole Eurozone however, the OECD forecasts that GDP growth will plummet from 3.2% in 2022 to just 0.5% in 2023, before recovering slightly to 1.4% in 2024. Europe’s proximity to the events in Ukraine and its dependency on Russian fossil fuels make it far more exposed to geopolitical events in Eastern Europe.

According to Eurostat, the EU's statistical branch, Ireland's GDP growth for the third quarter of 2022 was the highest in the Eurozone, with a 2.3% increase on the previous quarter.

Although our GDP growth forecast for the next few years is one of the highest in Europe, this is amplified by our aforementioned special relationship with GDP. In this case, we can take other measures into account, such as Modified Domestic Demand (MDD).

MDD is an attempt to show how the domestic economy is functioning, as it tallies up household and government expenditure, and investment in areas like construction and infrastructure. It doesn’t take the value of stocks, patents or anything else that doesn’t directly contribute to the Irish economy.

Data from the Central Bank shows that they forecast the MDD growth for 2023 to be 2.3%, down from a high of 5.8% in 2021. The OECD on the other hand believes that our MDD for 2023 will grow by just 0.9%, down from the 8% figure it had once predicted.

So, are we heading for bust?

The short answer is no. The long answer really depends on how you quantify the upcoming financial difficulties and whether you classify a drop in living quality, disposable income and real wages as a recession.

The Central Bank, in their Financial Stability Review, described the economic situation as a “severe and prolonged domestic macroeconomic shock”. They also highlighted the importance of Information and Communications (ICT) firms, i.e. tech firms, to Ireland’s economy, and how we are “particularly exposed to cyclical challenges faced by this sector”, such as job losses and decreased investment.

However, the recent redundancies might have been eye-catching, but they represented a small percentage of the overall ICT workers in Ireland, and there is nothing to suggest that other firms are likely to follow suit.

Indeed, unemployment, which is normally an indicator of a recessionary phase, has remained remarkably steady coming out of Covid. It has remained in the region 4.5% for all of 2022, and employers are finding it harder to find staff rather than the other way around.

The recent tech layoffs don’t share similarities with other tech crises in the past, such as the dot-com bubble, where fledgling tech companies were massively overvalued. The firms in this sector who hire the most workers in Ireland are industry stalwarts, and are generally able to weather minor wobbles in the market.

Indeed one of the other metrics that the CEPR uses, monthly industrial production, is on the rise in Ireland. The latest CSO figures show that there has been a 6.4% quarterly increase in industrial production, suggesting that the level of manufacturing and exporting has been largely unaffected by the changes in the economy.

However, there are numerous difficulties that exist now that didn’t a year ago.

The big one is inflation, which spread from energy inflation to impact everyday items. The 9.5% rate of consumer inflation is well beyond the 2% mark that most modern economies agree is the acceptable level.

Inflation has a number of knock-on effects on the wider economy also. It brings real earnings down while bringing up the salary expectations of workers, which in turn can lead to increased prices. Consumers who are having to spend more on energy, food and services will have less disposable income to spend on other, non-essential goods and services, which can impact employment and prices of those goods.

Even the ways in which governments fight inflation bring us closer to a recession. Interest rates and inflation have an inverse relationship, so raising interest rates in the face of rising inflation is seen as the most viable option for dampening the curve.

However, higher interest rates cool down economic activity. They are raised so that capital is harder to come by, people will start spending less money and will be incentivised to save more, all-in-all bringing down inflation due to lessening demand.

If you raise the interest rates too high or too quickly, however, you risk plunging an economy into recession as businesses are unable to borrow to drive innovation or their profits are hit from less demand and they begin shedding workers as a result. So, it’s easy to see how quick fixes can turn rapidly if not managed carefully.

There is a level of uncertainty to how the economy is going to react when the full scale of energy inflation comes to light. Thousands of consumers and businesses face astronomical energy bills over the next few months, despite government supports. Bonkers.ie research shows that the average gas and electricity bill has increased by just under €1000 in the past year.

Too early to tell

All in all, it might just be too hard to tell whether Ireland will fall into a recession, but the signs are better for us than our European neighbours.

We were left with a large ‘rainy day’ fund after a budget bolstered by larger than anticipated corporate taxes, which could and should help businesses and consumers over the next few months.

Our unemployment rate is very low and below the EU average, and our inflation level isn’t among the highest in the EU. But there is no question that the average Irish household will be worse off this year than last.

In essence, while our pockets might feel a bit lighter and the costs of goods go up around us, it could be a lot worse - and as the cause of inflation is rooted to temporary occurrences in the global economy, let’s hope that it too is temporary.

Read our other work

If you found this article interesting, you might enjoy some of our other work:

- Analysing ATM withdrawal data, we investigate whether we are moving to a cashless society.

- You can learn more about the Celtic Interconnector, which will serve as an underwater electricity exchange between Ireland and France, and how it will benefit our energy supply

- If you have any questions about the energy credits announced in Budget 2023, read everything you need to know here.

Get in touch

Do you feel we’re moving into a recession? Or do we just need to weather the storm? Let us know on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.